Educating Captured Apache Indians

Fort Marion, St. Augustine

1887

The Sisters' Role with Indigenous Peoples, Fort Marion

After the Civil War, the U.S. government focused on controlling Indigenous peoples, leading to the deportation of over 400 Apaches to Florida in 1886. The Sisters of Saint Joseph were contracted to teach the Apache children at Fort Marion, now Castillo de San Marcos.

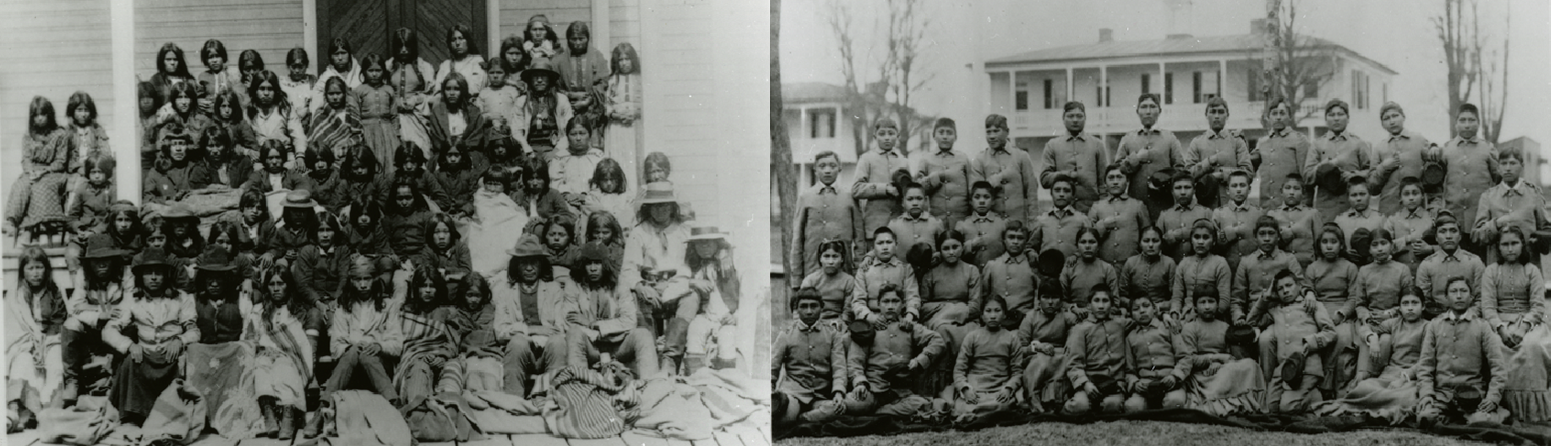

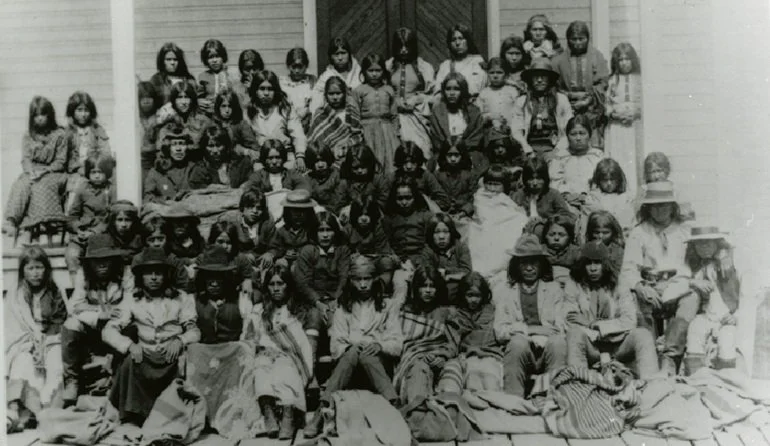

Apache Youth in Traditional Clothing, Courtesy of National Park Service.

Apache Detainment

In 1886, over 400 Apaches from the Southwest were deported to Florida by the U.S. Army. Most of them were sent to Fort Marion, now known as Castillo de San Marcos, in St. Augustine. Here, they were held against their will and forced to adapt to American customs.

Apache Youth in Traditional Clothing, Courtesy of National Park Service.

Apache Detainment

In 1886, over 400 Apaches from the Southwest were deported to Florida by the U.S. Army. Most of them were sent to Fort Marion, now known as Castillo de San Marcos, in St. Augustine. Here, they were held against their will and forced to adapt to American customs.

Geronimo and fellow Apache Indian prisoners on their way to Florida by train, September 10, 1886. Courtesy of Florida Memory Project

Building Trust with the Sisters

Sisters Alypius Laurent and Jane Francis were assigned to teach the Apache children. Sister Jane worked hard to learn their language and gain their trust. Soon, 25 Apache men, including their chief, voluntarily enrolled in the Sisters’ classes.

According to their letters, one day Sister Francis was sick and asked for a substitute. The Apache men rejected the unfamiliar teacher and refused to sit for her lesson.

The Sisters continued their work until April 27, 1887, when the Apache were moved to a larger facility in Alabama. This was in due, in part, to a Yellow Fever scare in Florida.

Education Amid Confinement

To alleviate boredom and attempt to "civilize" * the Apaches, the government established schools for the prisoners. In 1887, the Sisters of Saint Joseph were contracted to teach 15 to 68 Apache students for $7.50 per student. At the time, this job was highly competitive, and many were envious of the Sisters.

*While we at the Miguel O'Reilly House do not endorse or sympathize with racist or insensitive language, it is our responsibility to accurately report historical events as they occurred.

Sister Alypius Laurent

Page one of the SSJ’s Original Contract with Fort Marion

Acknowledging a Troubled Past

In a broader context, we believe it is crucial to acknowledge that the experiences of the American Indian population, both historically and presently, should not be taken lightly.

Some would argue that the Sisters contributed to the assimilation of Native Americans by accepting this job. Assimilation is a process that attempts to make people adopt customs, language, and ways of life of a different society. It's important to note that the Sisters today would not condone these actions, as they recognize the need for cultural preservation and Indigenous autonomy. As responsible historians, it is our duty to present history from diverse perspectives, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of past events.

Looking Back with New Understanding

Although the Sisters offered comfort and support, their work, along with similar missionary efforts, raises questions about cultural assimilation - an approach they would not endorse today.

A Complex Perspective

According to the Sisters' letters, many members of the tribe shed tears when they had to leave the Sisters. At the time, the Sisters felt that their actions brought comfort and positivity to a community dealing with the hardships of displacement and confinement. The Sisters' desire to offer support, education, and companionship to the Apache shows a complex perspective.

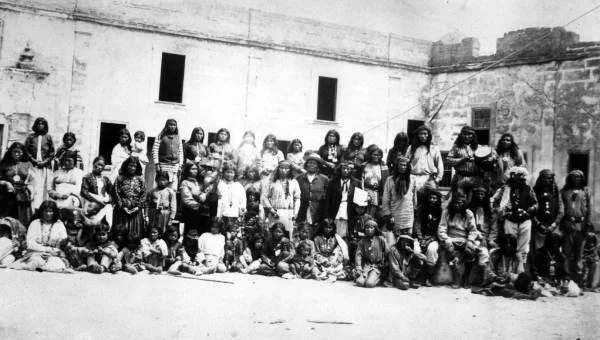

Group of Apache Indians, in their native costume, confined in Fort Marion. Courtesy of Florida Memory Project.